Three months ago, I was catcalled on my way to meet a friend for an early supper.

Stood in the small patch of green I was walking past, a man began shouting a variety of abusive comments towards me that commenced with “do you know what I would do to you?” I walked faster.

He then proceeded to join the pavement to follow me for about 100 yards, continuously hurling vile remarks. It was 6:20 pm in July, and therefore broad daylight, down a bustling A-road. Handfuls of people were around, shops were still open and rush hour carried on on my left.

After a while, two minutes before I reached the restaurant, he gave up on his mission. Once inside, I flopped down at our table. Looking at me curiously, my male friend I was meeting asked if I was alright. “Busy day at work,” I replied.

Days later, when I recalled the encounter with another friend, she asked why I hadn’t called her. I told her that to do so I would’ve had to release the keys I was holding between my knuckles inside my pocket and that the restaurant was barely minutes away. Our conversation soon returned to the mundane.

This was not the first time I had been in such a situation. I doubt it will be the last. And this was child’s play in comparison to some experiences women endure.

On Friday, Scotland Yard issued a new strategy aimed to protect women after Met officer Wayne Couzens kidnapped Sarah Everard while pretending to arrest her. The advice stated that women should “run into a house” or “wave down a bus” if they are approached by a male officer that they don’t trust. The same day, police, fire and crime commissioner for North Yorkshire, Philip Allott said on BBC Radio York that women needed to be “streetwise” and “learn about the legal process”. He has since conceded “’I have much to learn”.

These comments and strategies are insulting, glib and tone-deaf. Not only does it perpetuate the cycle of placing the responsibility on women to not get attacked, sexually assaulted or killed, but implies we aren’t already streetwise. That our lack of common sense invites this kind of behaviour. Trust us, we already have quite the arsenal of how we can, apparently, protect ourselves.

We know multiple routes back home. We carry our house keys between our knuckles. We hold our thumbs over the top of our open beer bottles. We turn on our location on our phones and text our friends when we get home. We are continuously told how to ‘do everything right’ and yet things continue to go wrong.

In June, and in response to Everard’s death, British singer-songwriter Josie Proto released a song entitled I Just Wanna Walk Home. She wrote it out of the exhaustion she felt at the measures she has to take to ensure, like many of us, she, firstly, gets home safely and, secondly, that if anything were to happen she would not get blamed.

In an interview on Annie Mac’s Future Sounds on BBC Radio 1, she said “I want to be a Mother and I want to have kids. I hate the thought of having to have that conversation with my daughter when my Mother had that with me, how can we go through two generations and it not be solved?” Her remarks struck a chord. My female friends and I have grown up with the concept of how to keep ourselves safe, but the thought of one day telling my daughter how to do so whenever she leaves the house is unthinkable. At the same time, I cannot envision living in a society where such a discussion would be rendered unnecessary.

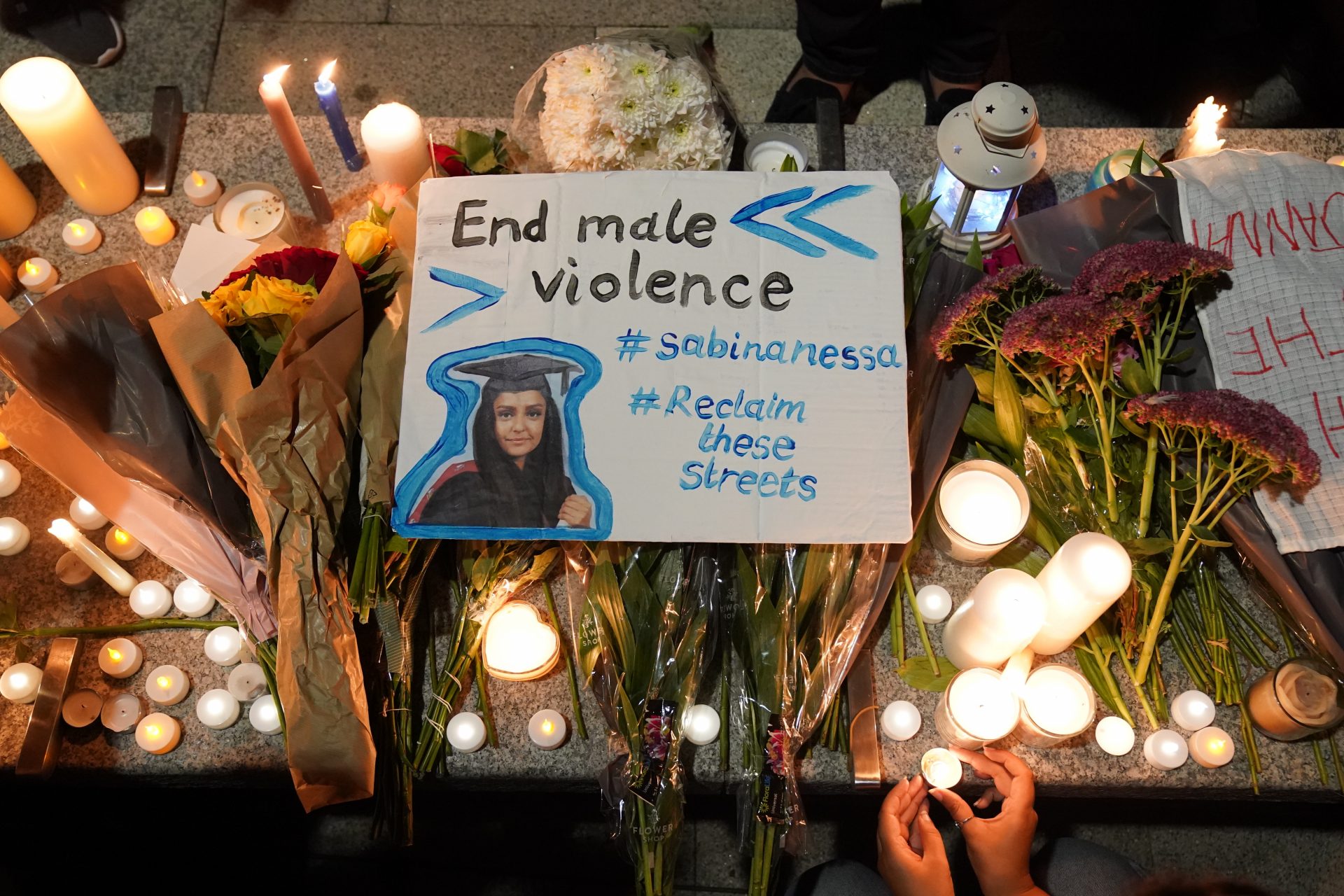

Since Everard’s murder, at least 80 more women in the UK have been killed by men, including primary school teacher Sabina Nessa. Only 1.6 per cent of rapes reported to the police in England and Wales result in a charge being made, and 52 per cent of police found guilty of sexual misconduct kept their jobs.

“You okay with where we are? ’Cause I see nothing changin’, it’s beyond frustratin’, I just wanna walk home,” Proto sings four times over the course of her song.

It is frustrating. Nothing is changing. And yes, we just want to walk home. But more importantly, we just want to be safe, and we’re not.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37